There really is no pressure like the pressure I’ve felt attempting to write someone else’s story—especially my father’s. I somehow feel as though I owe it to him to be honest, which means reliving and acknowledging the many secrets he held. It meant asking my mom for answers that I didn’t really want to know—because it would mean consciously shattering the comforting formation of memories I had selected of my father. That’s how we survive, right? Our brains are programmed to survive. Our brains intelligently and selectively filter out the really bad things. The stories we tell ourselves are supposed to make us comfortable so that we can move on, progress, mature. These stories are filled with a subconscious buffering that allow us to – at the very least – live with our past. Some traumas prove to be too much and create long lasting demons. My dad lived in this reality, or at least that’s the story I tell myself.

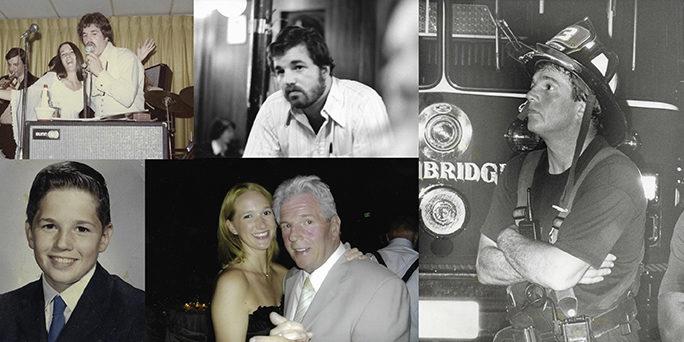

My father was a Vietnam vet, drafted at eighteen years old. He returned home after kicking a heroin habit. There’s an interesting study from this era that shows approximately 75% of those who had addictions while fighting the war were able to return home without any long-term addiction problems. My father was not in this percentage. The thought behind these findings is that once removed from a situation, the person no longer feels the need to escape, the threat is eliminated, and so is the desire to use. It didn’t work like that for my father. He returned home and did his best to reintegrate into society. By twenty-eight he had married my mother, and by thirty he had me. To support his new life and growing family, my dad did his best to provide, working different jobs which ranged from manual labor to eventually becoming a firefighter at age forty. Prior to that, however, he needed to do what needed to be done to pay the bills – so my dad worked at a few bars in Harvard Square.

One of my first memories shapes the story I tell myself about my father and guides the way I view my work as an addictions counselor. It was Saturday morning. We watched cartoons on Saturday morning – that was our thing. But my dad wasn’t home and I remember feeling extreme anxiety that he hadn’t returned from the previous night. It escapes me how I knew the details, but my mom was upset and it was clear that my father might be in trouble. I began perseverating on what I would say to the police officer to convince him to let my dad go. That morning, instead of focusing on the latest antics of Tom and Jerry, I was deep within the recesses of my imagination. At four, maybe five years old, I felt the deep responsibility to protect my father – to stand up for him, and make people see how loving and caring he was. I spent that morning going over and over what I would say. I knew that if I could just get them to see how much I loved my dad, then they would surely let him go. While I stared and waited for him to come up the stairs, I remember strongly believing that I would just need to explain that my father was good man. Because he was. My father picked me up and made me smile, and he smelled like butterscotch lifesavers and sawdust. He got angry every now and then, but he loved me. I knew he loved me and I knew how good my dad’s heart was. Kids are compassionate that way. My four year year old brain wasn’t able to understand that a good heart isn’t a get-out-of-jail-free card. I’m not even sure why I assumed that my father was in trouble, but I felt that fear from the tips of my toes to my messy bed head hair. Eventually my father came home, laughing his nervous laugh. He had one less tooth… but he was safe. I never had to put that speech to use.

I would grow to know that look; the nervous laugh and the glassy eyes. He spoke like he was using all the energy he had not to cry. I saw that look again when I was a Senior in college and he embarrassed me by getting kicked out of my game for being belligerent to the referees. He stood outside the gym, tears in his eyes, head hung, and his body hunched over. I just stood in front of him and asked “Why?” He looked at me from defeated, blood shot eyes. “Because it’s you, Jen,” he replied, and he began sobbing.

That was my dad. I knew that despite any opinion anyone had of him, he loved so hard it hurt. I truly believe that most people, if not all, are doing the best they can at any given moment, and that we are all essentially good. Our instincts are all the same and lean in the direction of survival. The instincts behind addiction are no different.

When my dad died, I was ready. He was ready. In my heart of hearts, I believe my dad prayed for it. It’s not that he ever told me that he wanted to die. My dad wasn’t a man of many words… and what he didn’t say felt like a thousand pound blackhole of grief. For my dad, that grief became too much of a burden to hold and he gave in and his body answered. There are a variety of diseases, parasites, funguses – a plethora of organisms and disorders -that take over the human body, paralyzing the soul like a songbird locked in a cage. With no expectation of improvement, one’s only relief becomes a hope for the end, a clutching onto whatever faith one has that there has to be something beyond the suffering.

Grief did this to my father — addiction was a symptom — encasing him in hardened calluses of anger, resentment, and disappointment. But that was not my father. To say that addiction stole my father would be an oversimplified statement. In the end it was my dad’s body that failed. In my experience and training, I believe that our bodies and minds are connected. The experiences and traumas we go through are held in our bodies. Without proper release, these experiences of stress create toxins that can do a tremendous amount of damage. In Chinese medicine, aliments that pertain to the respiratory system are often related to emotions of grief. My father ultimately died of pulmonary fibrosis complications—in addition to cirrhosis of the liver (a direct result of his inability to quit drinking). He was sixty-four years old. I said goodbye with my family by my side, playing Jeff Buckley’s version of Hallelujah and Teenage Wasteland on repeat. When he died, I felt relief. Relief that he was no longer suffering, relief that I could stop wondering when he would pass, relief that I could stop worrying… because I had been worrying about my father for as long as I could remember. And that’s what we as family members do. We worry based on the insane idea that we can somehow control our loved one with our anxiety.

At some point in my adult life, one of my father’s sisters said to me: “Your father never came back from Vietnam”. That statement hit me like a ten ton brick of truth. When I was preparing to write this piece, I wanted to make sure that I kept my father’s truth as forefront as possible. I wanted you to feel him – to see his heart, his smile, his quick wit. I wanted to put his anger, manipulation, gambling, lying, fear, and addiction in the shadows. That’s really all I’ve ever wanted to do. I’ve always had an intense desire to make sure my father’s heart was shown and felt. Where others saw these things in him, I saw pain. It’s always been pain. My father and I were extremely close, but I didn’t know my dad. My dad didn’t tell stories the way some dads do. My dad was a fairly quiet man; when he spoke it was typically either of importance or to add humor and wit (or a quick jab disguised as such). My dad was a tank. I thought he was the strongest man in the world. But I didn’t know him. No one knew him. Even his friends – who congenially called him “Harry” – didn’t know to search the obituaries for “James Harrington”.

When your soul is compromised – when you’re living in a constant state of stress – you look for anything to relieve the physical and mental torment. Drugs and alcohol accomplish this aim. When my dad’s tour in Vietnam stopped, the stress on his brain did not. Unless one actively does something to change, one will continue to live in a constant state of stress. Brains under stress do not make good choices. That’s why talking to someone is so important. My dad never let it out. He kept it in like a poison disguised as a strength elixir. My dad kept that world hidden. His secret kept him sick. My dad was a strong man…but what he possessed in physical strength, he lacked in faith. Addiction doesn’t constitute an absence of strength, it constitutes an absence of faith in one’s own worthiness.

The last time I saw my dad, I stood by his hospital bed knowing once I walked out of that room, I would never see him again. I couldn’t negotiate with the police or God regarding his goodness. I couldn’t plead with Death to bring him home with the promise that he would do better. It wasn’t Death’s fault. In truth, I had been preparing for that day my entire life. When you love someone in active addiction, it’s hard not to start grieving them before they go. But it never makes it easier. It was addiction that told my dad he wasn’t good enough or couldn’t do it. It was the demons in his head. My dad retreated inward and was never able to escape. At sixty-four my dad was gone. He was free and released from the grips of grief that ravaged him.

Today I try to help suffering individuals challenge their false beliefs – those inaccurate notions that have them convinced they can’t beat addiction, or aren’t good enough or worthy enough to have a life of sobriety. I work to shed light on the importance of hope and to instill a fire and desire to live. No matter how scarred our experiences, choices, and behaviors have made our view of ourselves, no matter how many mistakes we’ve made, there’s always something better. It’s tough and it takes work and effort, but there is literally never a reason for anyone to give up. We have to continue to see the light and find hope in the miracles of recovery, the power of transformation, and the importance of never giving up. My dad gave up, and it’s because he didn’t think there was any other alternative. He held in his pain and followed a false definition of strength – one that dictated that he couldn’t speak about his problems. So he swallowed them. He drank and drugged them away.

Jennifer Harrington is a therapist at the Process Recovery Center.